by Michael Sierra-Arévalo

In early 2015, the National President of the Fraternal Order of Police told the President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing, “now, more than ever, we see our officers in the cross-hairs of these criminals.”

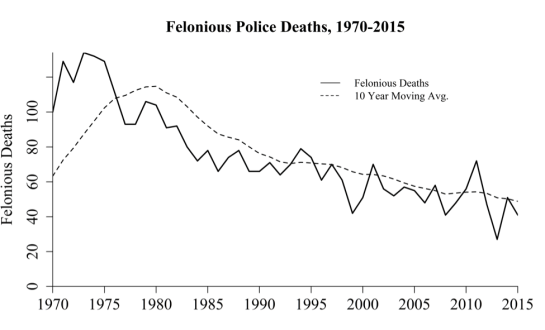

By the end of 2015, officers slain in the line of duty dropped almost 15% from the previous year.

Even with year-to-year fluctuations in the number of officers feloniously killed (i.e. not accidentally killed), overall trends in the FBI’s Law Enforcement Officers Killed and Assaulted (LEOKA) data suggests a profession that is growing less deadly over time.

Data notwithstanding, the rhetoric of the “war on police” persists in print and on the air, and the perception of a world full of violence that might strike at any moment is alive and well among U.S. police officers.

But though much attention has (rightfully) focused on how hypervigilance or aggressive training and tactics can negatively affect the citizenry, there has been little attention paid to the price officers themselves might pay by being socialized to see their world through violence-tinted glasses.

After spending hundreds of hours with police officers on patrol, at crime scenes, and in training session in three U.S. cities, as well as interviewing nearly 100 officers, I find that police officers engage in behaviors that they believe keep them safe but, in fact, increase the chances of injury and death in the line of duty.