Rising productivity, profitability and stock prices have long been heralded as signs of economic recovery from the Great Recession. Many segments of the population, however, have yet to experience any relief. Initially concentrated among the upper classes, gains in employment, income and wealth have gradually spread to middle America, but many groups, including race/ethnic minorities and young people have been left behind.

Rising productivity, profitability and stock prices have long been heralded as signs of economic recovery from the Great Recession. Many segments of the population, however, have yet to experience any relief. Initially concentrated among the upper classes, gains in employment, income and wealth have gradually spread to middle America, but many groups, including race/ethnic minorities and young people have been left behind.

Young people suffered a disproportionate share of job losses in the recession, and current trends suggest that they will be among the last to share in the benefits of economic recovery. Although a college degree offers some protections in a competitive labor market, it is not uncommon for recent college graduates (males somewhat more than females) to struggle with unemployment for many months following graduation. Many who do find jobs are underemployed – working fewer hours than they would like or in jobs for which they are overqualified

With an unemployment rate roughly double that of their white counterparts, young African American college graduates have even greater difficulty securing employment. The Center for Economic and Policy Research reports that in 2013, 12.4 percent of African American college graduates age 22-27 were unemployed, compared to 5.6 of all college graduates in this age group, and more than half of those who had jobs were underemployed. Those with degrees in the highly sought-after STEM fields (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) fared little better, with unemployment and underemployment rates of 10 percent and 32 percent respectively.

Read More

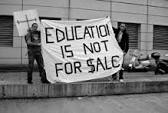

From time to time I write about the commercialization of higher education.

From time to time I write about the commercialization of higher education.