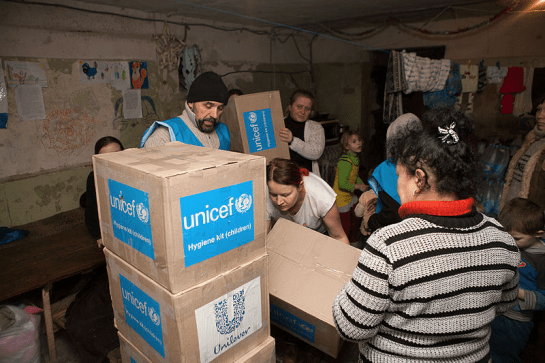

Image: Jason Hargrove via Flickr (CC-BY-NC-2.0)

by Nancy Galambos and Harvey Krahn

When we read about youth, titles like Generation X, Generation Me and Arrested Adulthood tend to paint an alarming picture of the younger generation in their 20s as directionless, floundering, and less likely than previous generations to become mature and productive citizens. In contrast, books like The Boomerang Age and Emerging Adulthood argue that more recent socio-demographic trends indicative of instability in education, employment, and living arrangements, as young people move from one job to another, seesaw between education and work, switch from one educational program to the next, and sometimes come back home to live with their parents are relatively benign.

There is no doubt that post-baby boom birth cohorts (labelled as Generation X, Generation Y, the millennials, and so on) have experienced such fluctuations, but are these experiences interpretable as floundering or do they merely reflect the freedom of young people in western societies today to explore their options until they find the best fit? Answers are important because we need to know whether shifts in how young people navigate the transition to adulthood are cause for concern and require appropriate policy interventions or whether they are simply reflective of a new and adaptive way of entering adulthood. In new research, we argued that fluctuations in employment and education statuses cannot be interpreted negatively as floundering, or more positively as exploring, unless we know something about their longer-term employment and career outcomes.