Today we are posting three articles related to work hours. In May, the Washington Posts’s “Wonkblog” argued that the next frontier of workplace legislation was “over when you work, not how much you make.” Their post provides some excellent context for the articles included in our panel. Our articles cover a wide range of topics. Naomi Gerstel and Dan Clawson’s lead article details the ways scheduling can impact workers in a variety of ways. Kyla Walters and Joya Misra describe the constraints placed on workers in the retail industry, and Brian Halpin details the use of last minute scheduling in a restaurant kitchen. Enjoy!

Controlling Time: Inequalities in Work and Organizations

by Naomi Gerstel and Dan Clawson

Control over one’s time is a critical resource for having a job and a family. But work hours and schedules, like the ability to control them, are highly unequal. Our book, Unequal Time, examines four occupations in health care—doctors, nurses, emergency medical technicians, and nursing assistants—to show the ways class and gender shape work hours, schedules, and the ability to control hours and schedules. Gender and class inequalities appear in workplace policy and negotiations over overtime and underwork, unpredictable cancelled shifts and added shifts, breaks, vacations, and family leaves.

Hours as Rewards & Punishment: Scheduling Practices in Clothing Retail

by Kyla Walters and Joya Misra

Retail is one of the fastest growing sectors of the service economy – and one that can include extremely unpredictable work scheduling. While retail positions are generally recognized as “bad jobs” because of their poor wages and benefits, scheduling makes these jobs particularly challenging. Our interviews with 55 clothing retail workers highlight the unpredictability of when workers receive the schedule, the amount of hours they’ll work, whether they’ll be called in last minute, and sometimes, when they can clock out. These practices are part of “just-in-time scheduling,” which link employment hours to customer demand. In this arrangement employers essentially expect workers to be available whenever the store gets busy.

Our study highlights that clothing retail workers experience their employers’ scheduling practices as difficult to navigate. Workers see their employers as both rewarding them with better schedules (since promotions and pay raises are rare) and punishing them by removing them from the schedule, rather than firing them. Scheduling appears to be clothing retail employers’ main means of disciplining workers.

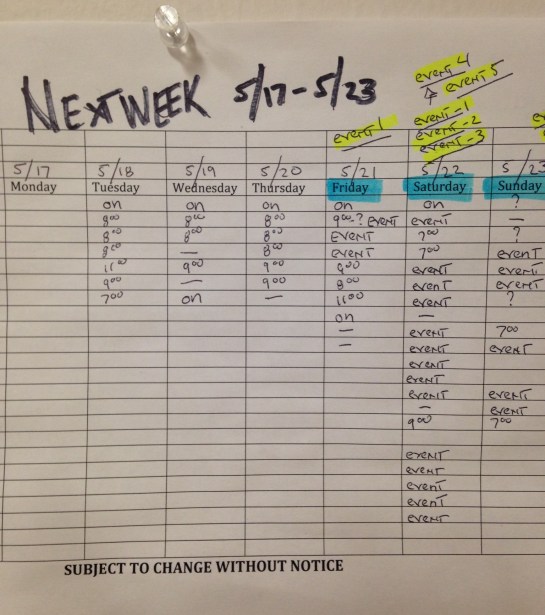

Subject To Change Without Notice

by Brian Halpin

As I walk up to the time clock to punch out for the day, I glance at the kitchen schedule posted next to the time clock. I notice that my shift times (as well as those of my coworkers) for all of the shifts for Friday through Sunday are missing actual times. Instead I see the word “event” or a question mark inserted as a placeholder. My coworker Josúe makes a comment as he punches his time card. “What the hell, it’s Wednesday. Michael [the kitchen manager] better fucking have my times up tomorrow [for the weekend] an’ he better not cut me on Sunday like he did last week.” As I look to see if I have any days scheduled for the following week, I notice the type in bold across the bottom of the schedule “SUBJECT TO CHANGE WITHOUT NOTICE.” Just-in-time scheduling, work hours irregularity, and cutting workers without notice are business as usual at California Catering where workers are subject to erratic and unpredictable scheduling manipulation.

Under Democratic governors, blacks are more likely to work, decreasing their earnings gap with whites

by Louis-Philippe Beland

Politicians and political parties play a crucial role in the US economy. The common perception is that Democrats favor pro-labor policies and are more averse to income inequality than Republicans. In recent research, I evaluate the impact of political party affiliation of governors (Republican versus Democratic) by looking at the following labor market outcomes: hours worked, weeks worked, employment, labor-force participation, and earnings. Given that there is an important and well-documented earnings gap between black and white workers, I investigate whether the party affiliation of governors affects this gap. This is an important issue given that a large proportion of black workers vote for Democrats.

I find that under Democratic governors, blacks are more likely to work, participate in the labor market, and work more intensively. This leads to an increase in the annual hours worked by blacks relative to whites, which decreases the earnings gap between blacks and whites.

Images of Work in Hollywood: “Nightcrawler” and “Good Kill”

It may seem strange to say, but we academics who study work sometimes get too caught up in the workplace itself. By that I mean that, much like the workers we study, we get so fixated on workplace events and processes that we forget to attend to the sphere of non-work. If we really want to understand the meanings that work acquires, then it behooves us to attend to the messages about work that are increasingly encoded in popular media –most notably, in film and TV. Here we can often find instances of what Paul Willis once called “penetrations,” or insights into the truth about work and inequality that debunk socially dominant myths.

As Exhibits A and B, consider two recent films that center on the struggles that workers confront in this era of neo-liberalism and new technologies. Both films derive their power at least partly from the sites they invoke, which lie at the very center of power and authority in the advanced capitalist nations. In the one case –“Nightcrawler,” starring Jake Gyllenhaal and Rene Russo— we get a vivid account of freelance cameramen trawling for lurid footage of violent crime, which they can sell to local TV stations wanting to jump start their ratings.

In the other case –“Good Kill,” starring Ethan Hawke and January Jones— the film centers on military officers assigned to work as drone operators, ordered to rain Hellfire missiles down at Afghani peasants vaguely suspected of being militants. These films seem on their face to be worlds apart. Yet in truth, both capture deeply troubling situations in which workers are compelled to produce and reproduce the very culture of violence that envelops us in our everyday lives. These films raise far reaching questions of concern to workers generally: What to do when morality and authority diverge –and how to achieve a modicum of agency and autonomy in a system designed to support neither.

The gulf between management theory and reality: A view from the American manufacturing heartland

Since I conducted research on manufacturing in the US Midwest in the early aughts, I’ve kept in contact with a few of my informants. One of them, Paul D. Ericksen, has 38 years of experience working in procurement and supply management, primarily in two household-name, multinational manufacturing corporations. Ericksen has been writing a blog on Next Generation Supply Management at IndustryWeek since April 2014, and I’ve been keenly following it.

The Ericksen blog is an object lesson in how wide the gulf is between the everyday problems facing manufacturing managers in the real world and the way academics represent management within mainstream management theory. By mainstream management theory, I have in mind the economistic literature based on assumptions that individuals are rational maximizers and markets are inherently efficient (as opposed to the sociological literature, which emphasizes how cultural institutions and power relations in the real world systematically undermine the maximization of efficiency).

Ericksen worked with many hundreds, perhaps thousands of factories that supplied parts and subassemblies to the Fortune 500 companies he worked for. Based on this experience, he highlights a number of ways in which deeply embedded forms of culture and power, in both the multinational corporate brands (prime contractors) and their suppliers (subcontractors), generate and sustain systematic inefficiencies in their organizations. (For academic studies that document and triangulate such outcomes with the views of other informants, see my colleague Josh Whitford’s book on the decentralization of American manufacturing, as well as my own study of routine inefficiency in factories.)

Reflecting on the defeat of Houston’s anti-discrimination ordinance

This past week, voters in Houston struck down Proposition 1, or HERO (the Houston Equal Rights Ordinance), which would have barred discrimination on the basis of race, age, military status, disability, sexual orientation, gender identity, and additional categories in non-religiously based organizations and institutions.

Several things come to mind in light of the vote.

HERO was drafted by Houston Mayor Annise Parker, certainly not the first female mayor or a major city but the first openly gay mayor of a major U.S. city. The bill’s opposition could be, in some way, opposition to an openly gay woman seen as “favoring her own,” a barrier many minority leaders face. While it is rare for straight, white male leaders get accused of passing legislation that benefits other straight, white men, it turns out that women and minorities are deemed as “selfish” and disliked if they attempt to promote other minority groups.

But would HERO have passed if a straight, white man drafted it? Maybe not because of the way HERO was framed by opponents.

Is there such a thing as “A Sociology of Leadership?”

by Scott C. Whiteford and Natasha M. Ganem

Searching for the term “leadership” in six key journals published by the American Sociological Association* from 1994-2014 brings up 31 peer-reviewed articles. This stands in stark contrast to the 2,848 papers published by these journals in total. By this measure only about 1% of sociological research is dedicated to leadership.

We have only found one book chapter that addresses the question of what a sociology of leadership might be. In Nohria and Khurana’s (2010) edited Handbook of Leadership Theory and Practice, sociologist Mauro F. Guillén provides a review of classical sociological approaches to the study of leadership yet directly acknowledges too that there is no such thing as a separate subfield of ‘the sociology of leadership.’

We are frustrated by this. Why is this topic off-limits in sociology? Might we consider Leadership as a substantive area in sociology? What would this look like?

When “Friends” Meets “Office Space,” Where Do Workers of Color Fit?

Adam Grant, an organizational psychologist at the Wharton School, has an op-ed in the New York Times that describes the decline in workplace friendships. Grant notes that compared to workers in other countries, Americans are much less likely to claim close friends at work or to see the workplace as a social space where close friendships are built. He refers to several important sociological studies in analyzing why this is so, noting that the nature of work has changed so that workers are more likely to switch jobs frequently and thus may not feel a close sense of association with colleagues.

Grant references classical sociologist Max Weber’s theory that Calvinism shaped the perception of work as a place where money is made and emotions are inappropriate. Importantly, however, Grant notes that ignoring the workplace as a site where friendships can blossom may rob us of important opportunities. Jobs can become more pleasant and workers more effective when they work with friends.

This is an interesting piece that has important implications for a work world that has changed significantly, and one where issues of diversity are of paramount importance. Sociologists have documented the myriad challenges that people of color encounter at work—stereotyping, tokenization, difficulty finding mentors, closed socialnetworks, discrimination, and others.